Selling your home for a profit can trigger capital gains tax, which is a tax on the increase in value (the gain) from when you bought the property to when you sell it. Fortunately, U.S. tax law provides special benefits for homeowners. In many cases, you can avoid or significantly reduce the capital gains tax on a home sale by meeting certain requirements or using smart strategies. The IRS offers a generous home sale tax exclusion that lets you exclude up to $250,000 of profit (or up to $500,000 for married couples) from taxation. This report will explain what capital gains tax is, how it applies to home sales, and proven ways to minimize or avoid this tax when selling a house. We’ll cover the IRS exclusion rule (Section 121), additional strategies like cost basis adjustments and 1031 exchanges, special situations (for married couples, divorced individuals, military personnel, and inherited homes), state vs. federal tax differences, record-keeping tips, and common mistakes to avoid. By understanding these rules and planning ahead, you can maximize your home sale profits and stay on the right side of the law. (Relevant search terms: capital gains tax on home sale, home sale tax exclusion, avoid capital gains real estate.)

What Is Capital Gains Tax on a Home Sale?

Capital gains tax is the tax you pay on the profit from selling a capital asset – in this case, your house. The gain is generally calculated as the selling price minus your “basis” in the home (typically your purchase price plus the cost of any improvements and certain expenses of sale). If you sell your home for more than what you paid (after accounting for improvements and selling costs), that profit is a capital gain and may be subject to tax.

For example, if you bought a house for $200,000 and later sell it for $300,000, your gain is $100,000, which could be taxable. Capital gains on real estate can be short-term or long-term depending on how long you owned the property:

- Short-term capital gains (if you owned the home for one year or less) are taxed at your ordinary income tax rates, which can be as high as 37% for top earners. For most home sales, short-term gains are rare since people typically own homes for more than a year.

- Long-term capital gains (owned more than one year) are taxed at special lower rates. The federal long-term capital gains tax rates for real estate are usually 0%, 15%, or 20%, depending on your income and filing status. High-income individuals may also face an additional 3.8% Net Investment Income Tax on large capital gains.

However, home sellers often qualify for a major tax break: if the home was your primary residence, you may be able to exclude a large portion of the gain from taxes entirely. The IRS’s primary home sale exclusion (under Section 121 of the tax code) allows single sellers to pay no tax on up to $250,000 of gain, and married couples filing jointly to exclude up to $500,000 of gain. This means many home sales result in no capital gains tax at all, as long as you meet the eligibility requirements. We will dive into those requirements next.

It’s important to note that this exclusion only applies to gains – if you actually sold your home at a loss, that loss is not tax-deductible in most cases (you simply have no gain to tax). In summary, capital gains tax on a home sale is a tax on your profit from selling the house. The tax rate depends on how long you owned the home and your income level, but a special rule for primary residences often lets you avoid capital gains tax on a large portion of your home sale profit. The key is understanding and qualifying for the IRS home sale exclusion, as explained below.

The IRS Home Sale Exclusion (Section 121)

One of the most effective ways to avoid capital gains tax on a home sale is to qualify for the IRS home sale exclusion, outlined in Internal Revenue Code Section 121. This provision lets eligible homeowners exclude a significant amount of their gain from taxation. Here’s how it works and how to qualify:

Exclusion Amount

If you meet the requirements, you can exclude up to $250,000 of capital gain from the sale of your principal residence if you are single (or file taxes separately). Married couples filing a joint return can exclude up to $500,000 of gain. In practical terms, this means you pay zero capital gains tax on that portion of profit. Any profit above the limit would be taxable.

For example, if a single homeowner sells at a $300,000 gain, they could exclude $250,000 and only the remaining $50,000 would be subject to tax. If a married couple has a $300,000 gain, it would be entirely tax-free since it’s below $500,000. This exclusion can be used repeatedly in your lifetime, but no more frequently than once every two years (more on this “frequency test” below).

Qualifying as a Primary Residence

The exclusion only applies to the sale of your primary residence – generally the home you live in most of the time. You cannot use it for a vacation house or purely investment property (though there are strategies if you convert a property to your main home, discussed later). The IRS considers various factors to determine your main home, such as where you spend the most time, your address on tax returns, voter registration, etc., but usually it’s straightforward if you only own and live in one house.

Eligibility Requirements for the Exclusion

To claim the Section 121 home sale exclusion, you must pass three key tests in most cases – the ownership test, the residence (use) test, and the look-back test:

- Ownership Test: You must have owned the home for at least 2 years out of the 5-year period ending on the date of sale. (That’s 24 full months or 730 days of ownership.) If you are married filing jointly, only one spouse needs to meet the 2-year ownership requirement. Ownership time doesn’t need to be continuous; it can be any cumulative 24 months within the five years before sale.

- Residence (Use) Test: You must have lived in the home as your primary residence for at least 2 years (24 months) out of the last 5 years before the sale. The 2 years of use do not have to be one continuous block – you could live in the home for a year, move away for a while, then move back for another year, for example. All that’s required is that the total time living in the home adds up to at least 24 months within the 5-year window. If you are married filing jointly, each spouse must individually meet the 2-year residence requirement to get the full $500,000 joint exclusion. Short absences like vacations still count as time lived in the home, so you won’t fail the test for taking a trip or a brief rental period, but lengthy rentals or moving out too soon can be an issue.

- Look-Back (Frequency) Test: The exclusion isn’t available if you already used it recently. Generally, you cannot have claimed the home sale exclusion for another home in the past 2 years prior to this sale. In other words, the sales must be at least two years apart. This prevents people from frequently flipping residences tax-free. For most folks who only sell a home occasionally, this is not a problem, but keep it in mind if you move often. (If you did have another home sale within 2 years, there are some partial exclusion exceptions covered later.)

If you meet all three tests – you owned the home for 2 of the last 5 years, lived in it as your main home for 2 of the last 5, and haven’t used the exclusion in the last 2 years – then you are eligible for the maximum $250k or $500k exclusion on your gain. This is often referred to as “Section 121 eligibility.”

Example – Meeting the 2-in-5 Rule: Suppose you bought a house 5 years ago and lived in it for 2 years, then rented it out for the next 3 years before selling. Because you lived in it for a total of 24 months within the 5-year period, you still qualify for the exclusion. If you’re single and your profit is, say, $150,000, the entire gain is tax-free. If your profit were $300,000, you’d pay tax only on the $50,000 above the $250k limit.

If Married Filing Jointly

Married couples can exclude up to $500,000, but there are special rules. To get the full $500k:

- Either spouse must meet the 2-year ownership test (only one needs to have owned the home for two years).

- Both spouses must meet the 2-year residence test (each must have lived in the home for at least two years).

- Neither spouse used the exclusion on another home within the last 2 years.

If one spouse does not meet the use test, the couple cannot claim the full $500k – typically they would only qualify for $250k (essentially the one spouse’s exclusion). For example, if a homeowner marries someone who hasn’t lived in the house, and they sell the house after the new spouse has lived there only 1 year, the couple would get only a $250k exclusion (because one spouse failed the use test). In contrast, if both had each lived there 2+ years (even if the title was only in one name), they’d qualify for the full $500k jointly. Planning note: if you’re married and want the full exclusion, ensure both partners satisfy the residency duration before selling.

Automatic Disqualifications: There are a couple of situations where you automatically cannot use the exclusion, even if the above tests are met. For instance, if you acquired the home in the last 5 years through a 1031 like-kind exchange (a swap of investment properties), the law prohibits using the primary home exclusion on that property. Also, expatriates who renounce U.S. citizenship may be disqualified. These are uncommon scenarios, but worth noting.

Claiming the Exclusion

If you qualify, the process of claiming the exclusion is straightforward. You simply do not include the excluded gain as taxable income on your tax return. If you receive a Form 1099-S from the closing (reporting the sale to the IRS) or if part of your gain is taxable, you’ll report the sale on Schedule D and Form 8949, only showing the taxable portion. But if your entire gain is within the $250k/$500k limit and you meet the requirements, you generally don’t have to pay any tax or even report the sale on your return (unless a 1099-S was issued). Always keep documentation in case of questions, but you won’t owe tax on the excluded amount.

Partial Exclusion for Special Circumstances

What if you need to sell your home but don’t meet the full 2-year ownership/use requirements? Life isn’t always predictable – you might have to move sooner due to a job change, health issue, or other unforeseen circumstance. The good news is that the IRS provides a partial exclusion in many of these cases, so you can still avoid tax on part of your gain proportional to the time you did own and use the home. The IRS is fairly lenient in granting a partial home sale exclusion if you have a valid reason for selling early. Common acceptable reasons include:

- Job Relocation: You took a new job or were transferred to a location at least 50 miles farther from your home than your old job was.

- Health Reasons: You had to move to obtain treatment for yourself or a family member, or a doctor advised a change of residence for health reasons.

- Unforeseen Circumstances: This is a broad category for unexpected events beyond your control. Safe-harbor examples the IRS accepts include death, divorce or separation, multiple births from the same pregnancy, loss of employment (and qualifying for unemployment), inability to afford the house due to a change in financial circumstances, damage to the home from natural disasters, etc.

If your situation fits one of these categories (or something similarly serious), you can claim a reduced exclusion. The amount of the exclusion is typically prorated based on the fraction of the two-year period that you did meet. For instance, if a single person had to move for a new job after living in the home for 12 months (which is 50% of the 24-month requirement), they could exclude up to 50% of the normal $250,000 limit – that is, $125,000 of gain – instead of the full $250k.

Example: You’re single and bought a home, but after one year you must sell because of an unforeseen circumstance (say, an ill parent you need to care for in another state). You lived in the house for 12 of the prior 24 months (half the required time). You would be allowed to exclude half of $250,000, which is $125,000, of your gain. So if your gain is $150,000, you pay tax only on the $25,000 portion that exceeds your reduced exclusion. If your gain is $125,000 or less, you’d owe zero tax.

Keep in mind, you still need to have owned the home for at least some period and the reason for sale must fall under the IRS’s guidelines for partial exclusion. You also cannot have taken another exclusion within the 2-year period (unless that earlier sale also met an exception). Partial exclusions are a one-time relief per unexpected move. It’s wise to keep documentation of the reason (e.g. job offer letter, doctor’s note, etc.) in case of any questions.

Overall, the Section 121 exclusion (full or partial) is the primary tool for avoiding capital gains tax on a home sale. By meeting the ownership and residency requirements – or qualifying for an exception – you can sell your home and potentially pay nothing in federal capital gains tax on a large amount of profit. Next, we will explore additional strategies and planning moves to further reduce or defer any taxable gains that exceed these limits or that apply in special scenarios.

Additional Strategies to Reduce Capital Gains Tax

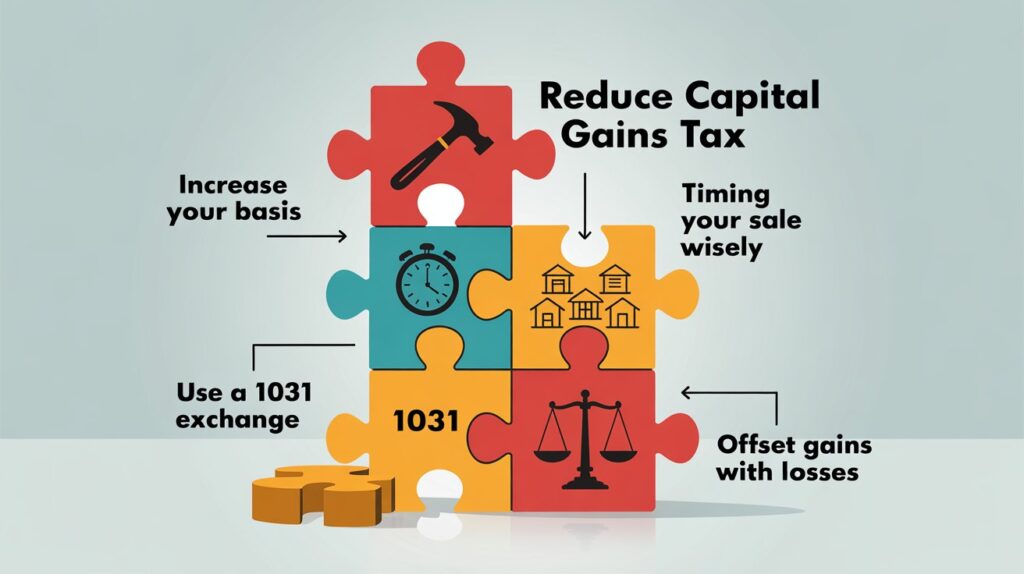

Even beyond the principal residence exclusion, there are other strategies and tax planning moves that home sellers can use to minimize or avoid capital gains taxes. These strategies can help in situations where you have a taxable gain (e.g. profit beyond the $250k/$500k exclusion, or sales that don’t qualify for the full exclusion). Here are some key methods:

1. Increase Your Cost Basis with Home Improvements

Your taxable gain is based on the difference between your selling price and your adjusted cost basis in the home. Cost basis is generally what you paid for the house, plus certain buying expenses, plus the cost of capital improvements you made. The higher your basis, the smaller your gain. Therefore, one strategy is to document and include all eligible improvements to raise your basis and reduce the taxable gain.

What counts as a capital improvement? Improvements are projects that add value or prolong the life of your home, or adapt it to new uses. Examples include adding a new room or deck, renovating the kitchen, installing a new roof or central air conditioning, replacing the windows, or major landscaping work. Routine repairs and maintenance do not count toward your basis because they just keep the home in good condition rather than adding value. However, if a repair is done as part of a larger remodeling project, it can qualify as part of an improvement.

Always keep receipts and records of any home improvement expenses. When it comes time to sell, these records will help prove your adjusted basis. Every dollar of improvement added to your basis is a dollar less in taxable gain. (Just note that if you received any tax credits or rebates for improvements, such as energy efficiency credits, you must reduce your basis by those amounts.)

Example: You bought your home for $200,000. Over the years, you invested $50,000 in capital improvements – you finished the basement, upgraded the kitchen, and added a deck. Your adjusted cost basis becomes $250,000 as a result. If you sell the home for $400,000, your total gain is $150,000 (selling price $400k minus basis $250k). Without counting those improvements, your gain would have appeared to be $200,000. So, by keeping track of improvements, you legitimately reduced your taxable gain by $50,000. This could be the difference between having a taxable portion or not, especially if you are nearing the exclusion limits.

In short, don’t overlook your home improvements – they can substantially reduce capital gains. Keep all documentation (contracts, invoices, permits) for improvements in a home file. Also track any selling expenses (real estate agent commissions, title and escrow fees, etc.) because those costs are deductible from the selling price when calculating your gain, effectively reducing the gain as well.

2. Time Your Sale for Maximum Tax Benefits

Timing can play a role in minimizing taxes:

- Qualify for Long-Term Status: Owning your home for more than one year generally qualifies you for long-term capital gains rates, which are lower than ordinary income rates. Virtually all homeowners aiming for the Section 121 exclusion will hold the property at least two years anyway.

- Meet the 2-Year Residency for Exclusion: If you’re close to meeting the 2-out-of-5 year rule for the home sale exclusion, consider delaying the sale until you satisfy it. For example, if you’ve lived in the home 18 months, and can stay another 6 months, doing so could turn a taxable sale into a largely tax-free sale.

- Use Two-Year Windows Repeatedly: Remember that you can use the $250k/$500k exclusion more than once in your life (just not more often than once every two years). Some savvy homeowners plan to “serially” convert and sell homes tax-free, especially in retirement.

- Plan Around Income Brackets: If you expect a significant taxable gain (above the exclusion), consider the timing within the tax year. Large gains can push you into higher capital gain brackets or trigger the 3.8% Net Investment Income Tax if your modified income exceeds certain thresholds. You might choose to complete the sale in a year when your other income is lower.

3. Consider a 1031 Exchange for Investment Properties

If the home you’re selling is not your primary residence (for example, it’s a rental property or a vacation home that doesn’t qualify for Section 121 exclusion), you cannot use the $250k/$500k exclusion. However, there is another powerful tax deferral tool available: the 1031 exchange. A Section 1031 like-kind exchange allows you to reinvest the proceeds from the sale of an investment property into a similar property and defer paying capital gains tax on the sale.

The catch is that this only applies to business or investment properties – not a personal primary home. But if you have, say, a rental house or second home that doesn’t meet the residence test, you could sell it and buy another investment property, deferring the tax. There are strict rules and timelines for a 1031 exchange, and if you previously used a property as your primary home and want to do a 1031, or vice versa, the tax treatment gets complicated. Always consult a tax advisor for 1031 strategies, as mistakes can nullify the tax deferral.

4. “Reinvestment” of Proceeds and Opportunity Zones

Many people ask if reinvesting the sale proceeds in a new house helps avoid capital gains tax. Under current law, simply buying another personal residence does not by itself defer or exempt the gain. The only reinvestment-based deferral for real estate is the 1031 exchange for investment property noted above.

However, if you do end up with a taxable gain, there are a couple of ways to reinvest gains to reduce taxes in a broader sense:

- Invest in a Qualified Opportunity Fund: If you have a large capital gain (from any source, including real estate) and you invest that gain into a qualified Opportunity Zone Fund within 180 days, you can defer recognizing the gain until 2026 (under current rules), and if you hold the investment for at least 10 years, any additional growth on that investment can be tax-free. This strategy is more relevant for very high gains and savvy investors.

- Offset Gains with Losses: If you have other investments that have built-in losses, consider selling those in the same tax year to offset your home sale gains. Capital losses can offset capital gains dollar for dollar.

Lastly, remember that the home sale exclusion doesn’t apply to rental or vacation homes unless you convert them to your primary residence for the required period. Some owners try a strategy of moving into their rental or second home for two years to qualify for the exclusion on sale, subject to rules for “non-qualified use” after 2008. Also, any depreciation claimed during rental years will be taxed (depreciation recapture). Despite these caveats, converting a second home to your main home for a couple of years before selling can still save a lot of tax compared to selling it outright as an investment.

Special Considerations for Specific Situations

Every homeowner’s situation is a bit different. Tax rules provide some special considerations and exceptions for certain circumstances such as being married, going through a divorce, serving in the military, or inheriting a property.

1. Married Couples (Joint Homeowners)

For married couples who own and sell a home, the biggest advantage is the $500,000 joint exclusion, which requires meeting the ownership and use tests (one spouse can fulfill ownership, but both must fulfill residency). Married couples should plan carefully to maximize this benefit:

- Ensure both spouses meet the residency requirement if you want the full $500k.

- If you sell in the same year you were married, you can file jointly and use the $500k exclusion (again, only if both satisfy the use test).

- If you are divorced as of the sale date, you generally each revert to a $250k individual exclusion.

- If both own separate homes, note that you only get one primary residence exclusion between you in any two-year period once married and filing jointly.

A surviving spouse can still claim the full $500,000 exclusion if the home is sold within two years of the spouse’s death, provided the other conditions were met up to that point. This provision helps a surviving spouse who needs to sell shortly after a partner’s death.

2. Divorced or Separated Individuals

Transfer of Home Between Spouses: Often in a divorce, one spouse will transfer their interest in the home to the other as part of the settlement. Such a transfer is not a taxable event – no capital gains tax is triggered at that time. The spouse who receives the home takes on the original cost basis of the entire property.

Using the Exclusion After Divorce: If the home is sold to a third party as part of the divorce, the question is whether one or both ex-spouses can use the $250k/$500k exclusion. If you and your spouse sell the home while still married and file a joint return that year, you can potentially use the full $500k exclusion together. If only one spouse meets the requirements, the exclusion might be limited.

If one spouse keeps the home, that spouse assumes full ownership and can eventually sell the house and claim a $250k exclusion if they meet the tests (though the ownership period of the other spouse is counted, so they don’t lose the ownership test). If under the divorce agreement the home remains the primary residence of one spouse, the other spouse may still be able to count that time for the use test, so both can qualify when it’s eventually sold.

3. Military Personnel and Certain Government/Peace Corps Employees

Military service members and some government or Peace Corps personnel often have to move on official orders, which can disrupt meeting the 2-year residence rule. To address this, there is a special provision for those on “qualified official extended duty”:

You may elect to “suspend” the 5-year look-back period for up to 10 years while on assignment. This means you could still meet the 2-out-of-5-year residency test even if you’re away from the home for a long time due to service. Essentially, you can claim the exclusion later without being penalized for not living there during your service.

Also, if you must sell before two years due to an official move, that could qualify under the partial exclusion for a work-related move. Note that any depreciation claimed while renting your home out (for instance, during deployment) is subject to recapture.

4. Inherited Homes and Estates

If you inherit a house, the tax treatment of a sale is quite different from a regular home sale. Typically, you receive a stepped-up basis to the fair market value on the date of the decedent’s death. That often eliminates most of the gain that built up during the decedent’s lifetime.

For example, if your parent bought a home for $50,000 decades ago and it was worth $300,000 at their death, your basis becomes $300,000. If you sell it for $305,000, your taxable gain is only $5,000. The primary residence exclusion does not carry over unless you yourself meet the 2-year rule by living in the property as your home. Most heirs simply sell the inherited property soon after inheriting, which usually results in little or no capital gain because of the step-up.

Federal vs. State Tax Considerations

Most of the discussion so far covers federal capital gains taxes on home sales (the Section 121 exclusion). However, states may also tax capital gains, and state rules can differ:

- State Adoption of the Exclusion: Most states with an income tax follow the federal treatment of home sales, meaning the excluded gain is also not taxed at the state level. But always check your specific state’s rules.

- State Capital Gains Tax Rates: If you do have a taxable gain above the federal exclusion, your state will tax that gain according to its own rates. Some states have no income tax, others have high tax rates on capital gains.

In planning your sale, there may not be much flexibility regarding state taxes, but it’s good to anticipate the potential bill. If you’re in a high-tax state and selling a high-gain home, you could owe a significant amount if part of your gain is taxable. If you’re relocating, be aware of which state will tax your income. Typically, the state where the property is located (and/or where you reside that year) claims the tax.

Record Keeping and Planning Ahead for Tax Efficiency

A critical part of reducing or avoiding capital gains tax is good record-keeping and proactive planning. By keeping the right documents and thinking ahead, you can position yourself to maximize exclusions and minimize taxes.

- Keep Proof of Purchase and Sale Costs: Retain the closing statements from when you bought and when you sold the home. This is needed to calculate your basis and your net proceeds.

- Document All Home Improvements: Keep receipts, contracts, and permits for any capital improvements. These costs increase your basis and reduce your gain.

- Maintain Records of Residence: If needed, keep evidence you lived in the home (utility bills, voter registration, etc.) to prove it was your primary residence.

- Plan Your Move Date Strategically: If you need the full 24 months in the home, consider delaying your move or the sale if possible. Or if you’ve moved out already, remember you generally have a 3-year window to sell and still meet the 2-out-of-5-year rule.

- Understand the Rules if Life Changes: Military duty, divorce, health issues, or other unforeseen events can trigger partial exclusions or special exceptions.

- Consult Professionals for Big Decisions: High-value homes, rental conversions, or inherited properties may require a tax advisor’s guidance.

- Use IRS Resources: Publications and worksheets can confirm your calculations.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Assuming You Qualify Without Checking: Verify you meet the 2-year ownership and use tests, plus the 2-year look-back rule.

- Not Documenting Home Improvements: Failing to keep track of improvements can cost you money by inflating your taxable gain.

- Mixing Up Exclusion Rules with Old Laws: Current law doesn’t require buying a replacement home or a one-time usage at age 55—those rules are outdated.

- Missing the Surviving Spouse Window: A widowed homeowner can still get the $500k exclusion if selling within two years of the spouse’s death.

- Forgetting About Depreciation Recapture: If you used part of your home for business or rental, the depreciation portion is taxable even if the rest is excluded.

- Not Understanding the “One Home at a Time” Rule: You only have one primary residence; you can’t claim the exclusion simultaneously on two homes.

- Selling Too Late After Moving Out: Generally, you have 3 years to sell and still meet the 2-of-5 requirement (unless military exceptions apply).

- Thinking a Second Home Sale Is Excludable: Vacation or second homes typically don’t qualify for the exclusion unless you convert them to your primary residence for 2 years.

- Neglecting State Taxes: Even if you avoid federal tax, some states may tax any remaining gain.

- Not Utilizing Partial Exclusion When Eligible: If you sell early due to relocation, health, or unforeseen events, claim the prorated exclusion.

- Failing to Report the Sale When Required: If a 1099-S is issued, you should generally report the transaction, even if no tax is due.

Conclusion: Keys to a Tax-Efficient Home Sale

Selling a home is a major financial event, but it doesn’t have to come with a hefty tax bill. With the U.S. tax code’s generous provisions for primary residences, many home sellers can avoid capital gains tax entirely on a large portion of their profits by qualifying for the Section 121 exclusion.

To recap the best practices for reducing or avoiding capital gains tax when selling your home:

- Make it your primary residence and meet the 2-year rule. This unlocks the $250,000 (single) or $500,000 (married) exclusion.

- Keep meticulous records of your purchase price, improvement costs, and selling expenses.

- Leverage special provisions if they apply: partial exclusions for early sales, military duty exceptions, etc.

- Consider additional strategies for remaining taxable gain: adjust your basis with improvements, use a 1031 exchange for rentals, or offset gains with losses.

- Avoid pitfalls by understanding the rules, verifying eligibility, and knowing you can’t double-dip on multiple primary residences.

- Plan ahead and consult professionals if needed.

By following these guidelines, you can sell your home with confidence that you’ve minimized any capital gains taxes. In many cases, the end result is zero federal tax due on your hard-earned equity. A little knowledge and preparation go a long way toward making the home sale process both profitable and compliant with the law.